Where the Turtles Return: Bribie Island’s Quiet Season of Renewal

As the first light of summer touches the sands of Woorim Beach, faint imprints appear on the shoreline — a series of slow, deliberate tracks leading to the water’s edge. They mark the arrival of the nesting season on Bribie Island, a time when the island’s quiet beaches become the stage for one of nature’s oldest migrations. For many locals, the season begins not only with the return of the turtles but also with a shared commitment to protecting them.

Each year, the Bribie Island Environmental Protection Association (BIEPA) brings the community together to celebrate the start of nesting season with the “Giant Turtle” event. Families, schoolchildren and volunteers gather to form the outline of a turtle on the beach, symbolising both the species’ struggle for survival and the care shown by those who share their home.

Yarun: A Place of Significance

Known traditionally as Yarun, Bribie Island is more than a holiday destination — it is a vital link in the life cycle of marine turtles. The island’s national park was established to safeguard its natural habitats, including the long, remote beaches where turtles lay their eggs each summer. Unlike the dense nesting colonies at Mon Repos near Bundaberg, Bribie’s beaches see fewer turtles, spread out across kilometres of coastline. This low density makes each nest more vulnerable to disturbance, but also more significant to the survival of the species.

The Ocean Travellers

Most of the nesting females that visit Bribie Island are loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta), part of the South Pacific population that is listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List. These turtles nest only once every three to four years, laying an average of four clutches of eggs before returning to their feeding grounds across the Pacific. Satellite tracking has shown that they travel vast distances — from reefs near Papua New Guinea and the Great Barrier Reef to the coastal waters of New South Wales and Moreton Bay.

Green turtles (Chelonia mydas), which are listed as Vulnerable, also nest occasionally on Bribie Island. Moreton Bay serves as a feeding and mating ground for this species, linking Bribie to a wider network of marine ecosystems that stretch along the Sunshine Coast.

Life in the Dark

Most turtle activity on Bribie Island’s beaches happens at night. Female turtles come ashore under cover of darkness to lay their eggs, digging nests in the soft sand above the high-tide line. Around 70 days later, the hatchlings emerge — small, determined and guided by the faint glow of the horizon as they make their way to the sea. Bright lights or torches on the beach can confuse them, leading them away from the water, while vehicles and footprints can block their path.

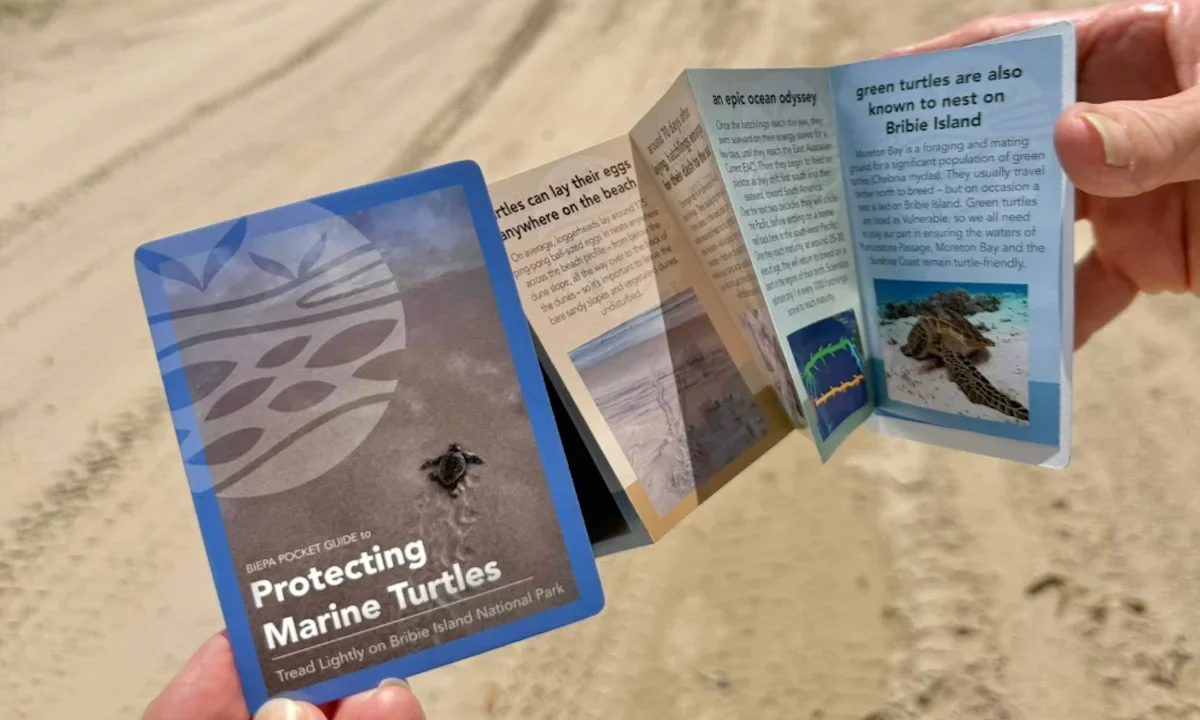

The Tread Lightly on Bribie initiative was created to help beachgoers reduce these risks. The tool provides tide information, maps and practical advice for responsible driving and camping along the coast. Its message is simple: avoid driving on dunes or above the high-tide mark, keep lights low, and plan trips around daylight hours. By doing so, visitors can enjoy Bribie’s beauty without disturbing the fragile nesting cycle taking place beneath their feet.

A Community of Care

Joshua Zugajev, Unitywater’s Executive Manager for Strategic Engagement, said the organisation supports environmental efforts like these through its Healthy and Thriving Community Grants Program. The program has helped fund BIEPA’s conservation activities, including the Giant Turtle event and volunteer monitoring on the island’s northern beaches.

This ongoing collaboration helps raise awareness about responsible beach use and supports the volunteers who collect valuable data on nesting patterns and species health.

Photo Credit: Supplied

The Journey Home

About 70 days after the eggs are laid, the hatchlings begin their dash to the sea, starting a journey that will take them thousands of kilometres across the Pacific Ocean. Carried by the East Australian Current, they drift southward and then eastward, feeding on plankton as they grow. It can take up to 30 years for a turtle to reach maturity and return to the same region to nest. Scientists estimate that only one in a thousand hatchlings survives to adulthood — a reminder of how fragile, yet resilient, this cycle of life truly is.

As another nesting season begins, Bribie Island once again becomes a place of renewal. From the first turtle track on the sand to the final hatchling’s sprint toward the sea, the island’s quiet rhythm continues — guided by care, patience and the hope that these ancient mariners will keep returning for generations to come.

Featured Image Photo Credit: BEIPA/Facebook